When first acquired the tapestries under discussion were described as ‘Sheldon’ because they presented many of the characteristics identified in the 1920s as those of the workshop at Barcheston. To that corpus they add three new scenes although their border patterns show details less commonly found. All these tapestries contain motifs found in work from the south Netherlands – the pattern on the arch for example36 – while the floral arrangements in the borders derive ultimately from the drawings of Cornelis Bos (c.1506-1555)37. The Fitzwilliam pieces also raise the same questions of origins, not only of place but also of design making and derivation discussed in connection with the variations in the tapestries showing Judith, all ascribed to the Sheldon workshop38. They are the difficulties associated with all items without distinguishing marks, such as the five Norwegian tapestries also in the Fitzwilliam Museum39.

The origin of a tapestry design is hard to establish unless one is fortunate enough to have either a contract naming an artist or an accomplished artist with a distinctive style susceptible to identification. Even with such clues the subsequent transmission or repetition of designs is difficult to trace40. This is especially the case when dealing with small-sized items which have the further complication that there was no requirement that they should be marked, either by a city guild or by the weaver. A sixteenth or early seventeenth-century provenance is rarely known for any small pieces, which are seldom descriptively inventoried; it may occasionally be indicated by a coat of arms sometimes associated with a date.

In the absence of obvious indications one turns therefore to comparative material for which there are two immediate possible sources. The work of Anthony Wells-Cole has revealed how much in English decorative art in any medium was dependent on the adaptation and use of Flemish or German prints41. Readily available Europe-wide and relatively cheap to purchase these prints were a boon to the small workshop, allowing it to economise on the cost of a designer. The practice was not restricted to smaller enterprises but can also be demonstrated in large-scale, famous tapestry series. The second option was to adapt scenes from compositions woven on a large scale. Though it is noticeable that the many small tapestries, whether known as Sheldon or clearly different in style and of a European provenance, rarely depict their subject matter in the same way as the more magnificent commissions of the same story that they faintly echo, ideas from both sources can be traced in the Fitzwilliam pieces.

In the case of the Tobias scenes none of the large-scale cycles of the story that existed by the probable date of the Fitzwilliam piece would seem to have exerted an influence42. Two less ambitious sets, both woven in Brussels around 1540, each show the homecoming in ways similar to the depiction in the much smaller Fitzwilliam example. One shows his new wife waiting in the background; 43 the other, illustrated only in the French photographic archive, pared the Return of Tobias down to its essentials but included the catching of the fish.

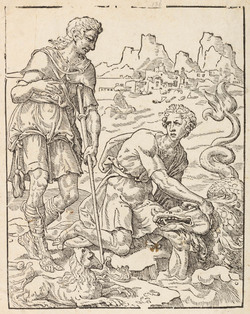

It is, however, at least as probable, given the strict adherence in small-scale work to presentation of a narrative in single scenes, that the Fitzwilliam examples were influenced by the work of the artist Martin Heemskerck (1498-1574). His rendering of Tobias wrestling with the fish is very close to that on the tapestry, seen also on the two single scene examples. His depiction certainly helps the reconstruction and interpretation of the very damaged scenes, previously the only examples of this theme, found in 1928 as patches on the arms of a sofa44.

Maerten van Heemskerck’s depiction of Tobias

wrestling with the fish

Museum Accession Number: m-h-1-201

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Detail, T.1-1953

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

A print source is also the probable inspiration for the scene of the sacrifice in the Life of Isaac cycle in the museum. The theme was enormously popular and, as in this and most smaller examples, usually depicted the moment immediately before the execution, not the approach to the place of sacrifice as in the large-scale series hanging at Hampton Court45. There are, however, so many potential print sources that isolating the exact model used in any of these small tapestries is almost impossible; the example shown is only one of many.

Detail, t.7a-1961

Detail, t.7a-1961

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Georg Pencz, Sacrifice of Isaac,

Museum Accession Number: 1876.12.16-115

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

By contrast the Fitzwilliam depiction of the Blessing of Jacob departs radically from many of the large-scale weavings of major Brussels ateliers of the 1540s where an architectural rather than a landscape setting was favoured. There is, however, a different interpretation in a slightly later example in the Fine Art Institute, Chicago46. The blessing is not the focus but is depicted in a vignette against a landscape background, in which Isaac lying in a canopied bed gives Jacob his blessing while Esau is still engaged in the hunt. It is very much the scene woven in the Fitzwilliam example and it is easy to appreciate how it could be adapted for use as the focus of a much smaller piece. More intriguingly still, there is a possible source that antedates the tapestries in which it is first seen, a drawing by Raphael dating to around 1522-1524, it contains more figures than the tapestry.

Isaac Blessing Jacob, print by Agostino

Veneziano of a drawing by Raffaello Sanzio

(1522-1524)

Museum Accession Number: P.5185-R

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Detail, T.7b-1961

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The theme was woven, with similar details, in a small piece now in the Toms Collection47. Here Isaac also reclines in a bed, but Rebecca stands and Jacob kneels to one side. Within a simple oval frame, Delmarcel considered the piece to be of Flemish or Dutch origin.

It appears again in a tapestry woven towards the end of the century, c. 1590, and some forty years later in another, very much larger weaving, both known only from the French photographic archive.

None of these pieces is susceptible to exact dating. Nevertheless it begins to look as though this might be a pattern in common use in workshops in territories north and east of Antwerp and thus, presumably, amongst the émigré workforce settled there48. Acquaintance with a drawing, already old by the time of its adaptation for use mid-century in the Brussels workshop of the well-known weaver Jan van Tieghem, reveals the longevity of a model which eventually passed into the pattern book of a small workshop.

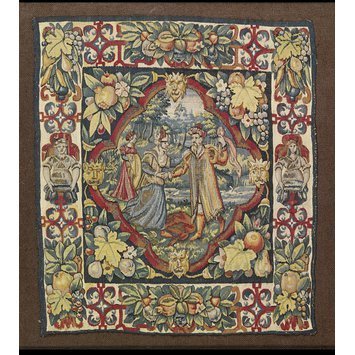

The enduring appeal of this iconography makes it easier to understand why there should be, as there often is, a close resemblance between small tapestries deemed to originate in continental workshops and those in England. Although the iconography is similar, the characteristics of such pieces differ widely – in design and in the level of skill of the workmanship executed in very different palettes. The point is illustrated by a set showing scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac in New York since 194149. Some of the same compositions appear also in a set of the Life of Jacob now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, where they are employed to illustrate different episodes50; the London set includes the blessing of Jacob, where Isaac is seated on a canopied throne51. The lobed strapwork in the border is alike in both sets and very similar to the Fitzwilliam examples.

Life of Jacob : Rebecca robes Jacob before the deception

T.181-1925, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

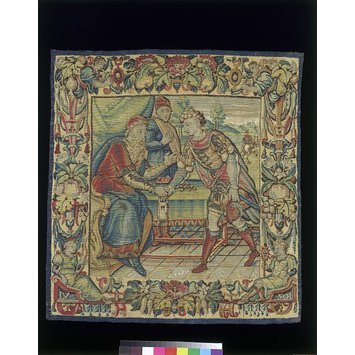

In the 1920s the Jacob set belonging to the Victoria and Albert Museum was a hotly debated candidate for inclusion in Sheldon work. Today both this and the Metropolitan set are regarded as Flemish, Dutch or even German products, the workshop unidentifiable. The same problem arises with weavings of the Prodigal Son; two sets in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London show exactly the same scenes but have different borders. On Wace’s criteria, one set would be classified as Sheldon, while the other is always held to be of Flemish manufacture52.

The departure of the Prodigal Son in tapestry

considered to be of continental origin,

T.278-1913, Victoria and Albert Museum,

London

© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum,

London

The departure of the Prodigal Son in tapestry

considered to be Sheldon work,

T.1-1933, Victoria and Albert Museum

London,

© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum,

London

-

Guy Delmarcel, Flemish Tapestries, London 1999, 169, 171. top

-

Suni Schele, Cornelis Bos: a study of the origins of the Netherlands grotesque, Stockholm 1965. top

-

Hilary L. Turner, ‘Some small tapestries of Judith with the head of Holofernes: should they be called Sheldon?’, Textile History, 41 (2) November 2010, pp.161-181, On-line at Maney Journals. top

-

Fitzwilliam Museum, T.1-1945 – T.5.1945. top

-

Helen M. Hughes, ‘Tapestries: producers, patrons and purchasers’, Textile History, 39 (1) (May 2008), pp. 108-110. top

-

Anthony Wells-Cole, Art and Decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England: the influence of continental prints 1558-1625, Yale, 1997. top

-

Paulina Jonquera de Vega and Concha Herrero Carretero, Catalogo de Tapices del Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid, Volumen I, Siglo XVI, Madrid 1986, Cat. 34; Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis, and Hillie Smit, eds., European Tapestries in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2004; T.P. Campbell, Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Tapestries at the Tudor Court, 2007, p.304a is closer. top

-

Sotheby’s London, 10 December 2003, lot 53. top

-

The pieces show Tobias and Sarah praying on their wedding night for deliverance from the evil spirit that had killed seven previous husbands, Tobias having burnt the heart and liver of the fish beforehand, chapter 8:4; Tobias anoints his father’s blind eyes with the gall of the fish, chap 11:12-13; illustrated in ‘The Sheldon tapestry weavers…’, Archaeologia, 78, p. 295 and plate xlix. top

-

T.P. Campbell, Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Tapestries at the Tudor Court, 2007, 281-293. top

-

Nello Fortini Grazzini in European Tapestries in the Fine Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Koen Broesens, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008, Cat.13. top

-

La Collection Toms Tapisseries du XVIe au XIXe siècle, ed. G.E.Cotton, Fondation Toms Pauli, Lausanne 2011, Cat. 91. top

-

Guy Delmarcel, ed., Flemish Tapestry Weavers Abroad: Emigration and the Founding of Manufactories in Europe, Louvain, 2002. top

-

E.A. Standen, European Post-Medieval Tapestries and Related Hangings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985, Cat. 30a-f; top

-

George Wingfield-Digby, The Victoria and Albert Museum, Catalogue of Tapestries Medieval and Renaissance, London 1980, pp. 64-65, T.180-185. Another set, with the lobed frame but very different borders, was sold in pairs from Littlecote House, Wiltshire, Sotheby’s London 20-22 November 1985, lots 460-462, whereabouts unknown. It included a seated Isaac blessing Jacob. top

-

A similar but larger piece was sold by Christie Manson, Woods, 15 December 1932, Lot 98, from ‘a famous continental source’, tapestry cushion cover 24 inches high x 40 inches wide, Flemish or Dutch, c.1600. Isaac seated is raising his hand to bless Jacob who kneels at his feet; a servant with a dish stands in the background and to the left. Esau is seen hunting. In a lobed panel with grotesque masks at the top, bottom and side, in each corner a bunch of fruit and flowers on brown ground enclosed within a border of strapwork, and branches of fruit and flowers on cream ground. top

-

Hilary L. Turner, ‘Tapestry strips depicting the parable of the Prodigal Son; how safe is an attribution to Mr Sheldon’s venture at Barcheston?’ Archaeologia Aeliana, fifth series, vol. 37, 2008, pp. 183-196, online at Tapestry sections depicting the Prodigal Son: how safe is an attribution to Mr Sheldon’s tapestry venture at Barcheston? top